Despite recent policy changes, the imprisonment rate among Black people remains the highest, and researchers say political trends may put progress in “jeopardy.”

This story was originally published by The 19th

By Candice Norwood, The 19th

Between the 1970s and early 2000s the United States saw a 700 percent increase in incarceration, which disproportionately targeted Black and low-income people.

Now, reform efforts in recent years are beginning to reduce imprisonment rates for the most affected communities. A new report by The Sentencing Project, a nonprofit research and advocacy organization, unpacks these declines and some of the policy changes driving them.

Black women and Black men saw the most significant differences. From 2000 to 2021, the imprisonment rate fell by 70 percent for Black women and by 48 percent for Black men. In comparison, Latinas saw an 18 percent decrease, Latinos saw a 34 percent decrease, White women increased by 12 percent and White men decreased 27 percent.

Even with these changes, the imprisonment rate among Black people remains the highest, and associations between crime, race and gender affect Black men and women in different ways. In 2021, Black women were imprisoned at 1.6 times the rate of White women, and Black men were imprisoned at 5.5 times the rate of White men, according to federal data cited in the report.

Researchers who spoke with The 19th News celebrated the downward trends as a positive step toward reducing mass incarceration and lessening the system’s grip on families of color, particularly Black families: from incarcerated Black fathers and mothers, to the loved ones at home — disproportionately women — who take on the remaining financial and caregiving responsibilities. However, the researchers were cautious about overstating the significance of the latest numbers.

“The work that’s been done to create reforms has had an impact, and so we should feel good about that. But it’s very much in jeopardy, especially given the response to the uptick in crime that happened during the pandemic,” said Nazgol Ghandnoosh, the author of the report and the co-director of research at The Sentencing Project.

Understanding incarceration trends

After years of rising incarceration, the recent declines over the last two decades are notable, particularly for Black communities. Sixty-three percent of Black people from a 2021 study had an immediate family member who was incarcerated, compared with 42.5 percent of White respondents. Almost 24 percent of Black people had three or more incarcerated family members, compared with 5.2 percent of White people.

The impact of incarceration on family structure is harrowing. An estimated 92 percent of incarcerated parents are fathers. About 60 percent of incarcerated women are mothers. As a result, relationships between children and their parents are severed. People with incarcerated loved ones are also more likely to experience mental and chronic physical illnesses.

The Sentencing Project report notes that the number of imprisoned Black Americans has decreased 39 percent since reaching its peak in 2002. For Black men the chances of imprisonment during their lifetime has decreased from a staggering 1 in 3 for those born in 1981 to a still troubling 1 in 5 for Black men born in 2001.

Even with improvements for Black men and women, it’s “important to put this in context,” said Sydney McKinney, executive director of the Black Women’s Justice Institute.

“The declines that we have seen do not match the significant increases that got us here, so there is still so much work to be done,” McKinney said. “Incarceration increased 700 percent since the 1970s, and now we’re seeing a 70 percent decline, which is not bringing us back to the levels we saw during the late ’80s and early ’70s.”

When it comes to women, another reality remains: While they represent less than 10 percent of the total incarcerated population, women’s incarceration numbers have increased at a rapid pace since the 1980s, growing from 26,378 incarcerated women in 1980 to 213,722 in 2016.

“Even if you consider the fact that the numbers for women have come down in recent years, if you look at a starting point in the ’70s, or 1980, and then look at the endpoint being today, you would see that the growth for women is more than the growth for men,” Ghandnoosh said.

Women are proportionally more likely than men to be incarcerated for a drug or property offense, and Black women are affected the most, even as their numbers in prisons and jails decline. The current rise in incarceration for White women and decline among Black women can be attributed to reform efforts focused in urban areas, while incarceration in rural areas, particularly rural jails, continues to grow.

A snowball of other factors also led to higher rural incarceration, said Monica Smith, an associate director of advocacy and policy at the Vera Institute of Justice’s “Beyond Jails” initiative.

“I used to work for a project and we focused on the rise of rural incarceration, and what we saw was that there was the rise in like opioid drug use and then also a breakdown of traditional industries such as coal mining. So those two things kind of came together almost like a perfect storm to criminalize poverty,” Smith said.

The policies driving incarceration declines

It can be a challenge to assess how specific reforms have affected national incarceration trends, but Ghandnoosh points to California, New York and New Jersey as key areas making inroads.

For example, New York’s drug law reforms implemented in 2009 eliminated mandatory minimum sentences, letting judges give shorter sentences, probation or drug treatment to people convicted of drug crimes.

A Vera Institute analysis determined that in New York City the changes prompted a drop in recidivism and racial disparities for drug convictions and led to more eligible defendants being referred to diversion treatment programs.

The Sentencing Project report also noted that New York City notably decreased its jail populations, assisted in part by the state’s 2019 law eliminating cash bail for most misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies. Other states, including Illinois, California and New Jersey have also implemented bail reform.

Another segment of the carceral system experiencing change is community supervision in the form of probation and parole.

Probation involves a person who has been convicted of a crime whose sentence has been suspended. Parolees are individuals who have served a portion of their sentence behind bars and are granted conditional release from the facility.

The conditions of a person’s probation or parole can include hefty fees, curfews, job requirements, travel restrictions, and meetings with a probation or parole officer. These limitations often act as a trap that can send people back to jail or prison, McKinney said.

“These restrictions set them up for greater risk of violations. One thing for women in particular is thinking about how they navigate managing child care duties and getting to their required meetings: Do they have enough money to pay for the transportation to get to their meetings, and take care of their families?” McKinney said.

The Sentencing Project report found that the number of people under community supervision fell from a peak of 5.1 million in 2007 to 3.7 million in 2021. The report did not include a gender breakdown, but a 2023 analysis by the nonprofit research group Prison Policy Initiative found that 33 percent of women in state prisons were on probation at the time of their arrest.

Mona Sahaf, the acting director of Vera’s Reshaping Prosecution initiative, said that many of the policy changes chipping away at incarceration rates are happening at the county level.

“All these district attorneys are elected locally in these little jurisdictions, particularly in more urban areas that are bluer and where some of the prosecutors run on a platform saying, ‘I’m looking to decarcerate and I’m looking to find ways to make the system more humane,” Sahaf said.

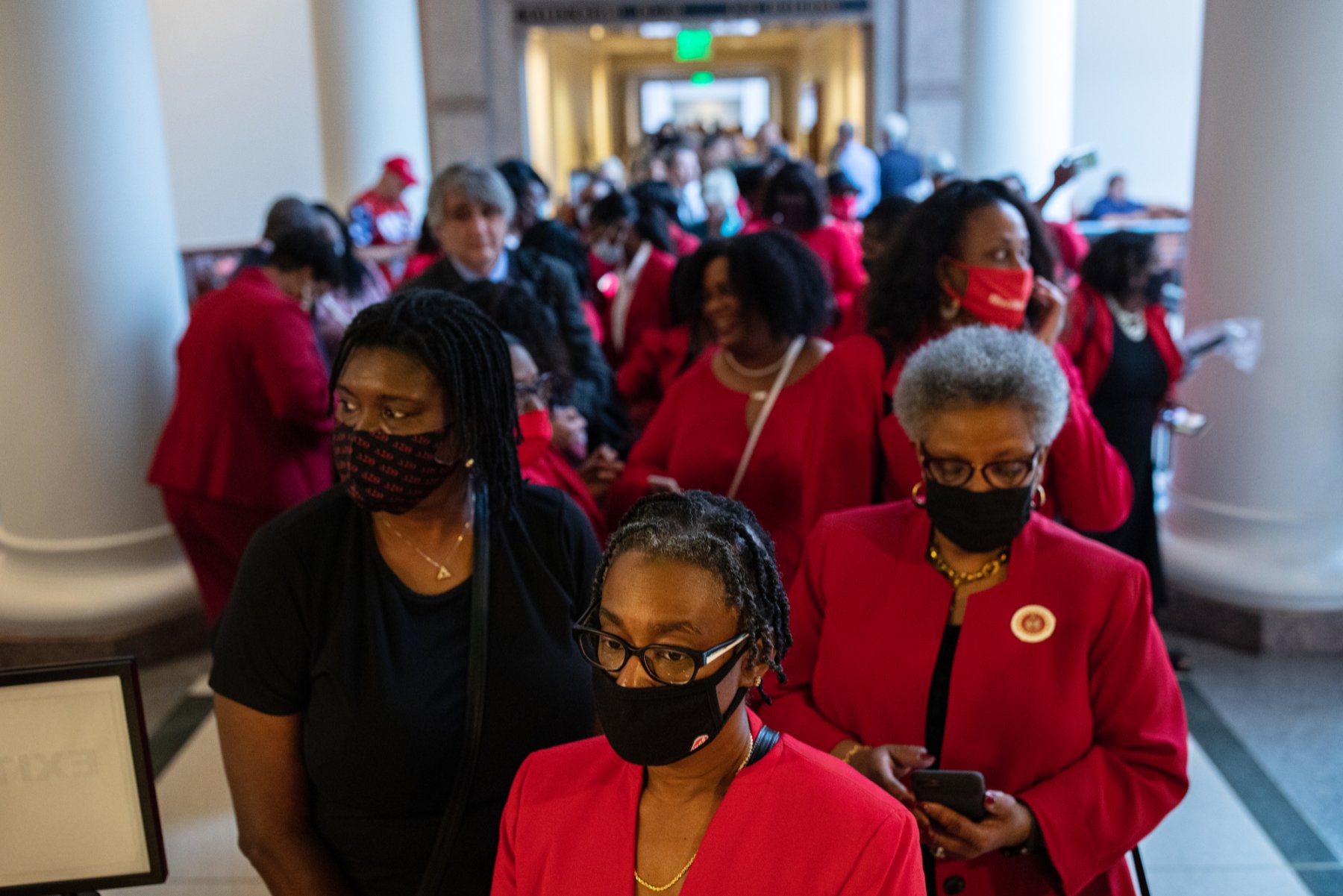

(Tamir Kalifa/Getty Images)

Remaining challenges for reform

As some states and counties work to rethink their approach to crime and incarceration, progress is limited. The country is experiencing a resurgence in tough-on-crime rhetoric calling for more harsh action from officials in response to upticks in crime during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In 2020 violent crime rates rose nationwide, though numbers indicate that this pattern slowed the following year. Crime rates have been used as a political talking point to criticize reform efforts by officials in Democratic-run areas. However, Republican-run and Democratic-run cities saw murders rise at similar levels during the pandemic.

One analysis by the Brennan Center for Justice found that poor and historically disadvantaged communities bore the brunt of the rise in violence in 2020 and that acts of violence were concentrated among younger people. Significant economic hardship during that period is one key factor for violent crime, but there’s more than one cause, two researchers wrote for The Washington Post.

As jurisdictions grapple with public safety concerns, “a bipartisan backlash to criminal justice reform includes a Congressional proposal to expand mandatory minimum sentences for federal drug offenses and a Congressional resolution overturning Washington, D.C.’s criminal code overhaul,” The Sentencing Project report said.

This year, New York announced plans to roll back bail reforms to give judges more discretion on how defendants are released. Another example is Connecticut, which between 2016 and 2021 revived its efforts to grant clemency, or a reduced sentence, to people serving time in prison. But in April a state board announced it would suspend commutations.

“We’re just seeing a lot of what I would call political grandstanding and using the perception of rising crime to make changes without much thought,” Smith said. “In some places, advocates are losing those battles for reform, and it’s unfortunate.”

National advocacy organizations like Vera Institute and the Black Women’s Justice Institute have long called for more community-based approaches that center communities most affected and address the root causes of crime in the United States, including economic and educational disparities.

Gender-specific solutions are an important component of this work. Most incarcerated women have experienced physical or sexual assault during their childhood. They also experience higher rates of economic hardship prior to entering jail or prison.

Diversion efforts targeted toward men, particularly Black men, can also be effective. Groups such at Black Man Rising based in New Orleans can help create spaces for young men and boys at risk of incarceration to address the emotions and trauma they experience in their daily lives, whether it be racial or socioeconomic.

Historically harsh sentencing and punishment for crimes has not increased public safety and does not address recidivism, but the cycle of tough-on-crime policies continues to repeat, reform advocates said.

“It’s really unfortunate for these kinds of technocrats who should be making decisions based on evidence and research to instead be making decisions on politics,” Sahaf said.

Blog dedicated to news and viewpoints from Black journalists who support, and inform, communities of color.

Original content, and curated articles, are posted and updated daily.